Brocket Hall Estate is a fine example of 18th century parkland in the English county of Hertfordshire. The stately home in its grounds had been residence for two British prime ministers. The expansive land around the hall with its ancient and exotic trees had been later developed into two championship golf courses. Both now carry the names of these politicians - The Melbourne golf course and The Palmerston golf course. However, even this famous luxury resort had been affected by a terrible blight in British countryside: illegal dumping of waste.

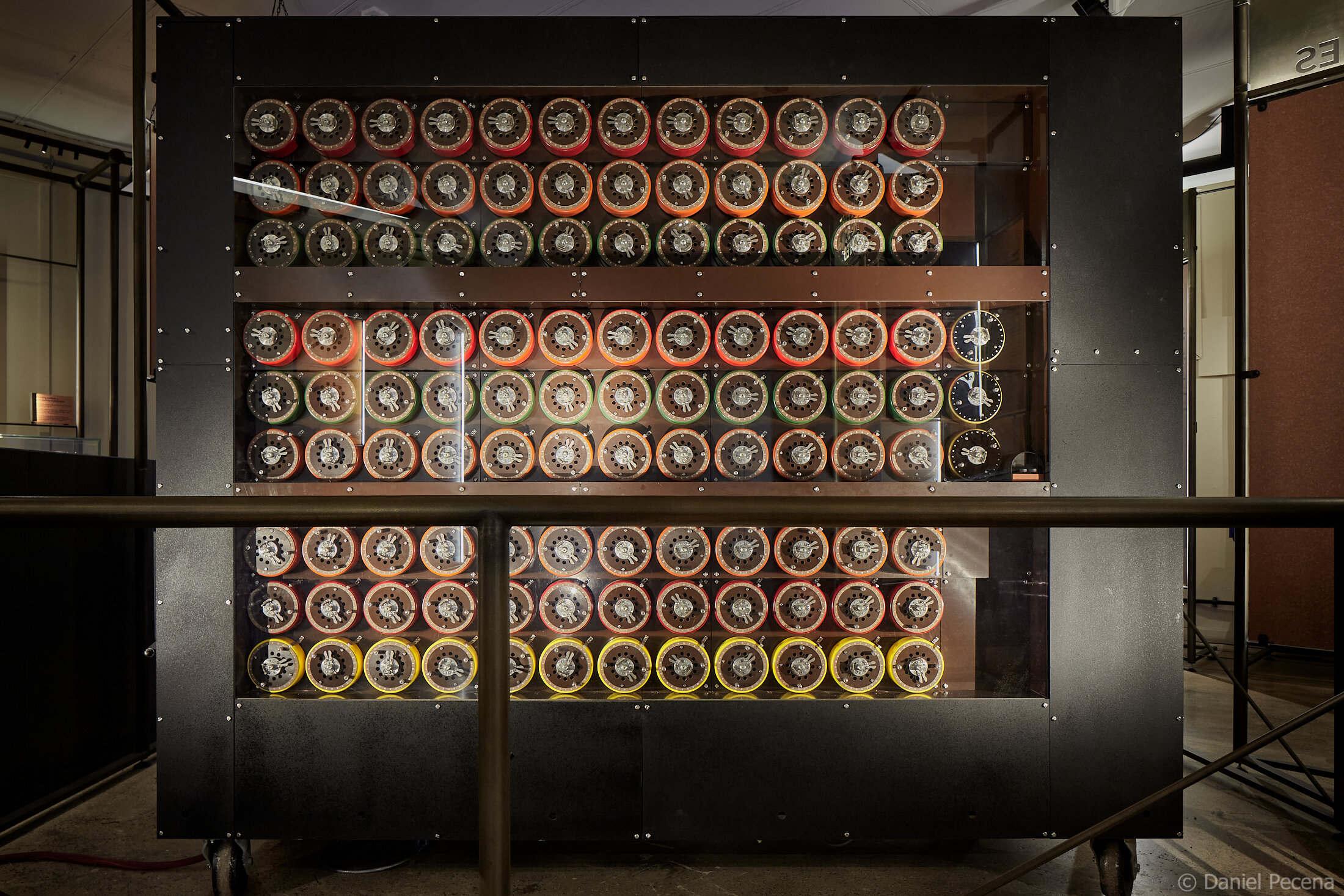

Plate I

Last year on Christmas Eve I joined my friends for an enjoyable walk in English countryside. Part of the route, which is also public right of way, was leading through Lea valley and Brocket Hall Estate. In the woodland called Flint Bridge Plantation, visible from public footpath we glimpsed rubbish covering vast area of the forest floor. The extent of waste spread in this woodland was completely incomprehensible. We recently walked the same route again and seeing the damage to environment repeatedly I decided that I need to document this area photographically.

Landscape painting and to a large extent landscape photography is dominated by “pretty pictures”. However, some artistic endeavour is devoted to depicting landscapes during or after human interventions. Such representations are certainly not idealised views with ability to enhance positive emotional states. Quite the contrary. But these perspectives should inform the public, document the scope of some problems or critique systems in our civilisation.

Quick search online revealed that this particular fly-tipping incident happened here over several days more than five years ago (in 2018). In the BBC article it was estimated that there is 400 tonnes of rubbish on one acre of land with potential cost of a clean up at £80 000. Even though the Fly Tipping on Private Land Pilot Fund had been introduced in 2018 unfortunately this fund is not available for private parks and estates. It may be that the cost of much needed clean up operation is really prohibitive but the fact is the waste is still here and causing inevitable damage in this place.

This is however, not an isolated incident. The whole UK is affected by actions of unscrupulous individuals or companies illegally disposing of rubbish to fields, forests or streets. According to organisation Countryside Alliance, “there was over one million incidents of fly-tipping recorded in 2021/2022 alone. This is equivalent of 124 incidents of fly-tipping every hour.” DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs) recorded in the same time 37 000 incidents involving ‘tipper lorry load’ size with the cost of clearance £10.7 million.

What could be the cause of this problem? Well, it could partially be the official policies themselves as in 2017 some UK county councils very much increased the prices of bulky waste dumping and at the same time the construction and commercial waste was being banned from council recycling centres as more rigorous segregation prior to dumping was introduced. In other words, tighter regulation around correct waste disposal may have led to massive increase in fly-tipping. There was also one more occurrence that affected how the UK deals with its waste. In January 2018 China banned import of waste from other countries. Until that time it was standard practice to export various waste there not only for the UK but also for other European countries, the USA, Australia and Japan. According to article The waste ban in China: what happened next? Assessing the impact of new policies on the waste management sector in China written in Environmental Geochemistry and Health (Na song, Iain McLellan, Wei Liu, Zhenghua Wang & Andrew Hursthouse) “One of the main reasons for the ban of waste imports is the serious environmental contamination and the associated human health derived from handling Waste electrical and Electronic equipment (WEEE) imports.” The export of waste, also known as global plastic waste trade, continued to other Asian countries like Malaysia. And in a lot of instances according to Greenpeace organisation which commissioned the report into this practice, it was being dumped and burned illegally. Then the export of waste from the UK found different routes to different countries, some actually in Europe (like for example Netherlands or Poland).

Returning to the forest with the tonnes of waste on the forest floor the conclusion for the natural world is that it had been contaminated by various inorganic materials which have a lasting negative impact on local ecology and wildlife. As it is very hard to decompose it makes the top soil layer impenetrable by new plant roots. The water from rains is also retained by the waste and is not draining properly down into the soil. Absorption of minerals that normally end up in the soil decreases and as a result the number of microorganisms that make the soil fertile declines.

The public naturally call for larger penalties or longer sentences for people committing these crimes and that may be a good deterrent but at the same time that would only be addressing these issues partially. What is also needed is change in policies, perhaps with incentives and streamlining the systems in dealing with waste disposal in general. These days the local problem can be a global problem and vice versa.

Plate II

Plate III

Plate IV

Plate V

Plate VI

Plate VII

Plate VIII

Plate IX

Plate X

Plate N